Introduction

Previously, I focused on a few Union Forts in a section of the Petersburg siege earthworks. The Petersburg siege (from June 15, 1864, to April 2, 1865, some 292 days) was associated with constructing earthworks on both Union and Confederate sides, each trying to gain an “edge” in the defense or offense mode; during this extended siege, skirmishes, infantry frontal assaults, and flanking movements occurred. However, no real breakthrough happened for much of the siege. As part of the third offensive (see Earl Hess’s excellent book In The Trenches At Petersburg Chapters 7 & 8), plans were made to mine a section of the Confederate defensive line at Pegram’s Salient as part of an assault and breakthrough on the Confederate lines.

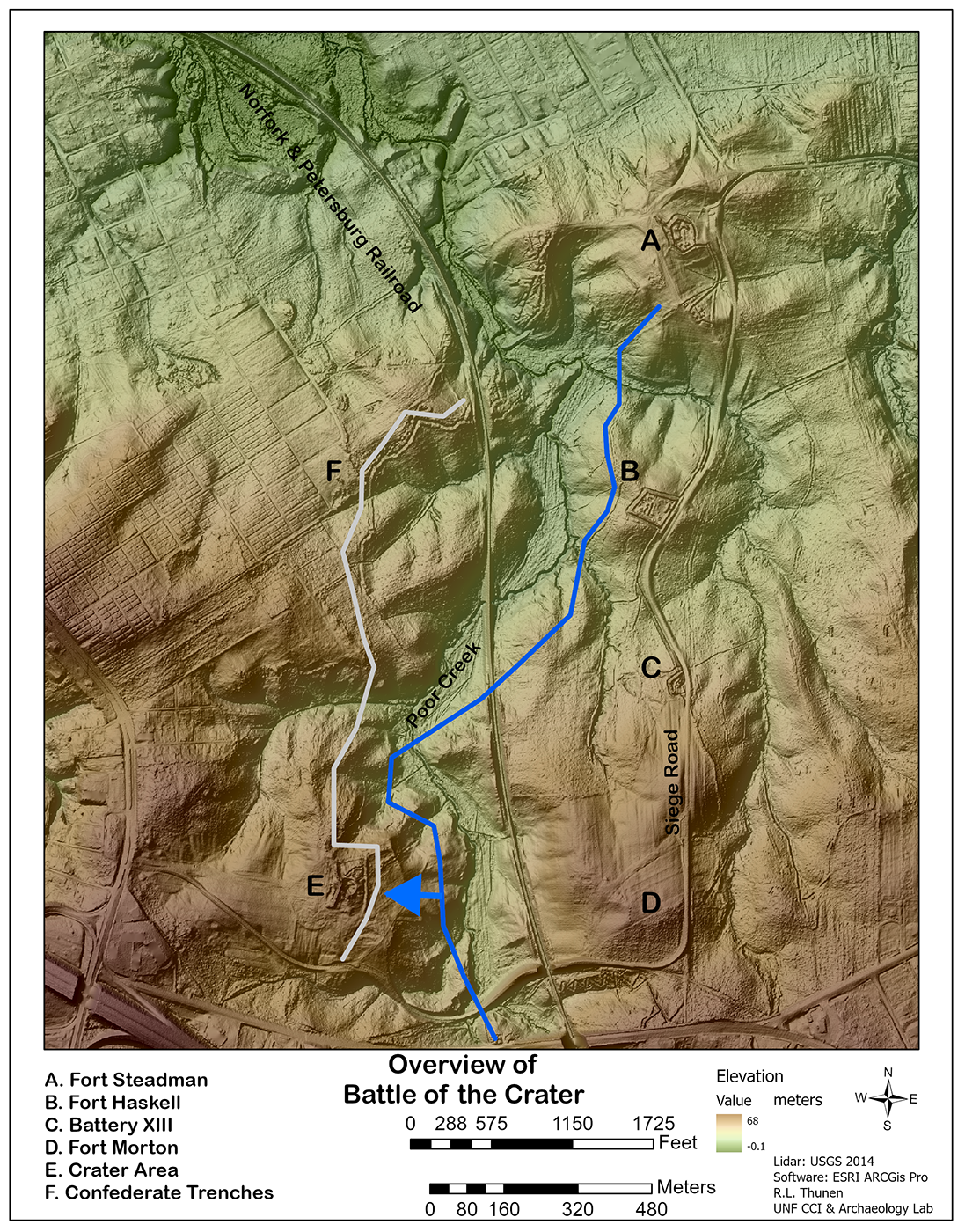

The lidar images were created using ArcGIS Pro and Surfer to give you the best views of this tragic event. The battle on July 30, 1864, is etched into the landscape at Petersburg: the landscape remembers. Nine sheets of Lidar data comprise the larger section of the Battlefield. The images below come from the intersection of four lidar data sheets. The Digital Elevation model in Figure 1 (below) displays the area of the Crater (E) and the Union positions to the east (the Blue Line), as well as three Union Forts (A, B, D) and an associated Artillery Battery (C). Fort Morton was a Union fort that had started as a 14-gun battery earthwork in the summer of 1864 and was built out into Fort Morton by that fall. The Gray Line represents the Confederate defenses. The Union attack is symbolized by the Blue arrow with the mining tunnel just above the arrow. Both Confederate and Union lines extended further north and south than depicted here.

Timeline: the Battle of the Crater

The Union Army, under the command of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, and the Confederate Army, under General Robert E. Lee, were engaged in a protracted siege of Petersburg, the backdoor to Richmond, Virginia. The Union Army also hoped to seize control of the five railroad lines that came into Petersburg cutting supplies to troops and communities. Union Colonel Henry Pleasants, a Mine engineer officer, proposed a plan to tunnel under the Confederate lines and detonate explosives beneath their fortifications. The Union high command approved the plan, and work began on a tunnel on June 25. On July 27, the Union tunnel was completed, stretching over 500 feet long. The coal miners of the 48th Pennsylvania packed the tunnel with approximately 8,000 pounds of gunpowder into two branches of the tunnel under the Confederate line. The Confederates had sunk countermines and failed to intercept the Union tunnels.

On July 30 at 4:44 a.m. in the morning (after the fuses failed to detonate at 3:30 AM, the explosives were detonated, creating a massive crater roughly 125 feet long, 50 feet wide, and 30 feet deep (Figure 3). The blast killed some 352 Confederates, injuring many more soldiers, destroying fortifications, and creating chaos in their lines. By 6:00 am, Union troops, including soldiers from the United States Colored Troops (USCT), poured into the breach created by the explosion. However, they became trapped in the Crater instead of pushing forward and up the flanks due to poor planning, bad leadership, steep crater walls, bad footing caused by the clay soils, and the lack of troop coordination. A counter-attack by Confederate forces quickly converged on the Crater, setting up a deadly crossfire from their remaining fortifications. The Union troops were able to get troops up toward the Jerusalem Plank Road behind the Crater, flanking the Crater, but no further reinforcements made it beyond the Crater. The Union troops in the Crater suffered heavy casualties as they were exposed in the blast crater and could not advance or find cover.

The Confederate defenders/survivors and reinforcements from the flanks successfully repelled the Union assault. Union troops, demoralized and exhausted, began to withdraw from the Crater. By 1:45 pm, the battle had ended. The Confederate forces retained control of the battlefield—Union casualties number around 3,800, including many USCT soldiers. Confederate losses were estimated at approximately 1,500. General Grant called off the Petersburg offensive, recognizing the failure of the Battle of the Crater to break the Confederate lines. Grant called the attack a “miserable failure” and the “saddest affair I have witnessed in the war…..So far.” (Hess, 105). The Battle of the Crater is notable for its unique tactics involving tunneling and using explosives. While initially successfully creating a breach, the Union’s inability to exploit the advantage and subsequent mismanagement led to a devastating defeat.

Maps

Figure 2 (below) was done in Surfer using lidar data for the area of focus. A million and a half data points were used to create the topographic map below. This gives you a good view of the immediate area around Pegram’s Salient. Salient means prominent or conspicuous: projecting or pointing outward, and was a term used to describe landforms/or defensive fortifications projecting out along a defensive line. The higher ground of the Salient provided an advantageous firing position for the Confederates, while ironically, the lower ground to the east may have aided the concealment of the Union’s tunneling operations.

Figures 2, 3, 4, and 5 were created as separate maps with their cut lidar data points to develop the individual maps. This allows the gridding of the data to create a topographic map unique to the area. Focusing on the context of the view enables a better-detailed map of the Crater by using the data points from the immediate area. Each map used cut data from the broader lidar data sheets to enhance the map detail for the viewer.

Figure 3 (below) is a topographic map of the Crater as of Lidar flight 2014. Some two thousand five hundred data points were used to create this map. The elevations are in meters, so 40 meters elevation equals 131.23 feet (a major elevation at ground level), and 38 meters is 127.67 feet (in the Crater), which means roughly speaking, the current depth of the Crater is over 6 feet in-depth. This is a far cry from the initial force of the blast. According to Hess, the explosion created “an irregular hole in the earth 125 feet long, 50 feet wide, and 30 feet deep.” Five times the depth of the crater now. It was like a mini volcano erupted, throwing clay, sand, and rock into the air. Men were blown apart; some were buried alive, and some just vaporized. Hell had opened for a moment, and both the Confederate and Union soldiers were stunned by the explosion. But time and erosion have started to heal the wound known as the Crater.

Figures 4 & 5 show closeups and context of the Crater and Mine Tunnel created using Surfer and 94,000 Lidar data points to develop the Crater and Mineshaft. Figure 4 is the area without labels for you to examine the landscape. There is a lot to see and interpret. What do you see? Remember that the data is from 2014, 150 years after the Battle, and a lot has happened to the Battlefield; it is not frozen in time.

Figure 5 (below) is a 3d Bird’s eye view from above the tunnel, looking northwest up to the Crater. This dramatic illustration shows the power of the blast. Figure 5 is my interpretation of those features based on scholarship by Hess and others detailing the day’s events. Some of the features on the map below are the lidar point cloud data revealing slight elevation differences in the landscape so that you can “see” sections of the collapsed mine shaft. If you go to the battlefield today, you can walk down to the mine entrance and see the damage from the explosion above the entrance. My location of the Ventilation Shaft area is speculative on my part but based on Hess’s Map on page 84. Additionally, the two countermine shafts by Confederates are good candidates; however, the features could be trenches associated with the rebuilding of the defensive earthworks (perhaps over collapsed shafts?); after the failure of the Union to take the area, the Confederates did rebuild the defensive earthwork (behind the Crater). Or the two features could be later landscaping modifications (walkways, stairs, places to sit) after the war, associated with visitors visiting the Crater. The area around the Crater today reflects earthworks repaired by the Confederate forces and later landscape modification to allow tourists to view the Crater and the surrounding landscape, starting as early as the 1870s and onward.

Figure 6: Shows the Crater today (2021), with the Crater aging from the blast and slowly backfilling through erosion. Almost immediately after the war ended, veterans, family members, and the curious traveled to see “The Crater.” At that time, human remains could still be viewed scattered within the Crater’s clay soil and debris. Today although a shadow of the violent explosion and fierce close-quarter fighting lingers, there is still power in this sunken area where men fought and died. And the landscape remembers.

The Siege of Petersburg ended on April 2, 1865, as the Union Army broke (“The Breakthrough”) the Confederate line north of the Crater to the northwest of Fort Welch and Fort Fisher.

References, Links, Etc.

Book references

Edwin C. Bearss 2012 The Petersburg Campaign: The Eastern Front Battles, June-Agust 1864, Volume 1, Savas Beatie, California

Earl J. Hess 2009 In the Trenches at Petersburg: Field Fortifications & Confederate Defeat. University of North Carolina Press. Chapel Hill.

James M. McPherson 1988 Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, Oxford University Press. New York.

Websites

NPS site for Petersburg Battlefield

The American Battlefield Trust has an excellent phone app for touring the battlefield. Their website for the battle is here Petersburg Battlefield.

Other important websites for the battle can be found here:

The Seige of Petersburg Online

A Geologist examines the soil associated with the Crater area. Nicely done.

Geology of the Battle of the Crater

The opinions offered here are the author’s and do not mean an endorsement by the UNF Archaeology Lab, Center for Community Initiatives, or the University of North Florida.

Maps used in this blog were created using ArcGIS® software by Esri. ArcGIS Pro™ is the intellectual property of Esri and is used herein under license. Copyright © Esri. All rights reserved. For more information about Esri® software, please visit www.esri.com.” Surfer® software, the intellectual property of Golden Software, is used herein under license Copyright ©Golden Software. For more information about Surfer, please visit https://www.goldensoftware.com/products/surfer.