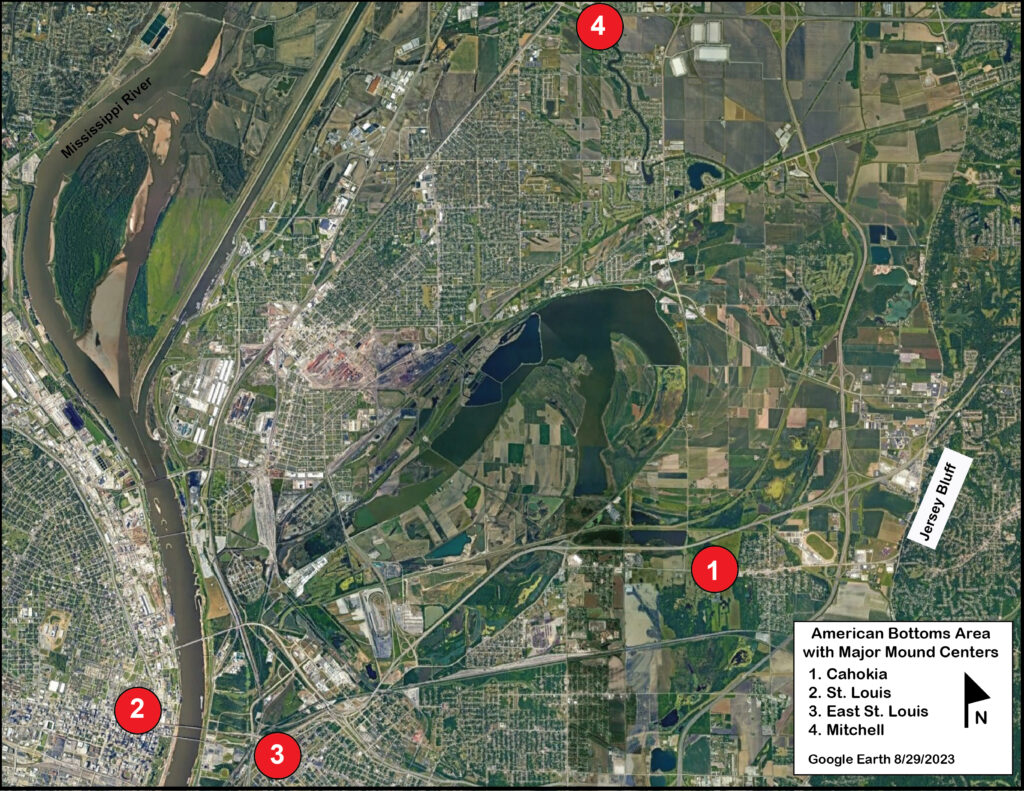

Reader beware! I have gone down a rabbit hole. That rabbit hole is Cahokia Archaeology. Over the years, archaeologists have done an extraordinary amount of field excavations and surveys in the area known as the American Bottoms. Cahokia is the largest archaeological site in this area. However, three other major mound complexes linked to Cahokia now largely destroyed are: St. Louis Complex, East St. Louis Complex, and the Mitchell Complex, to Cahokia’s north, provided a network of communities that made the American Bottoms (Figure 1) the most populated area in late prehistoric North America. Estimates place between 15,00 to 20,000 people living around Cahokia between 1050-1350 AD. The American Bottoms is defined by the Jersey Bluff to the East and the lower elevation bluff (in St. Louis) across the Mississippi River to the west. It is an area with rich alluvial soils, small and large lakes off of the Mississippi River, and a diverse ecological food spectrum for native peoples to hunt and gather from, as well; the soil provided a good base for horticultural gardening, especially for maize.

This blog entry examines Cahokia’s plazas through lidar. Each plaza has its own biography with several different chapters, for example, initial occupation, prehistoric land modification, use as a plaza, further modifications, then the areas used later by historic farmers, further modification for flood control, housing developments, and archaeological research to mention a few of the events which have altered the landscape.

I. Plazas at Cahokia

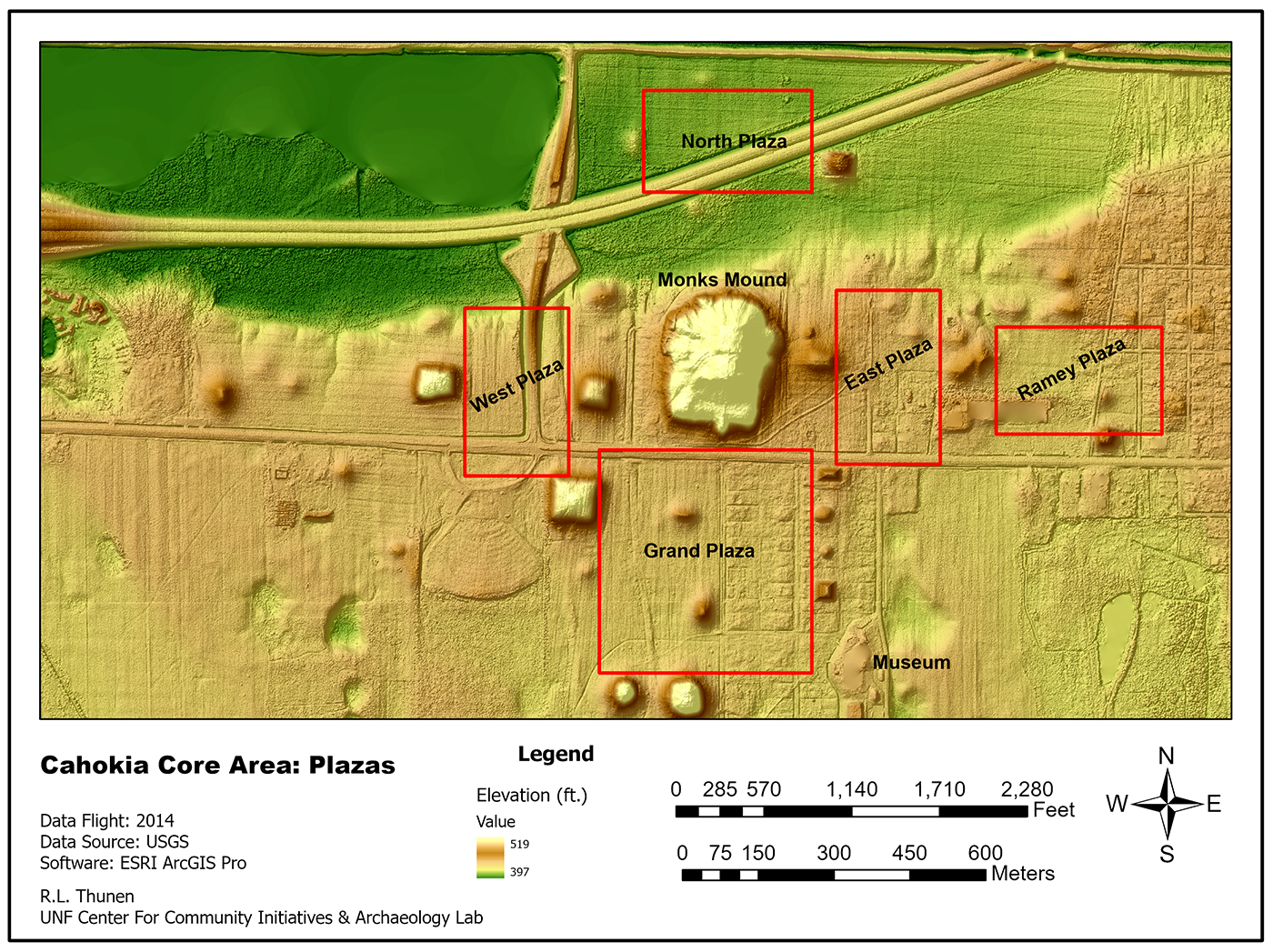

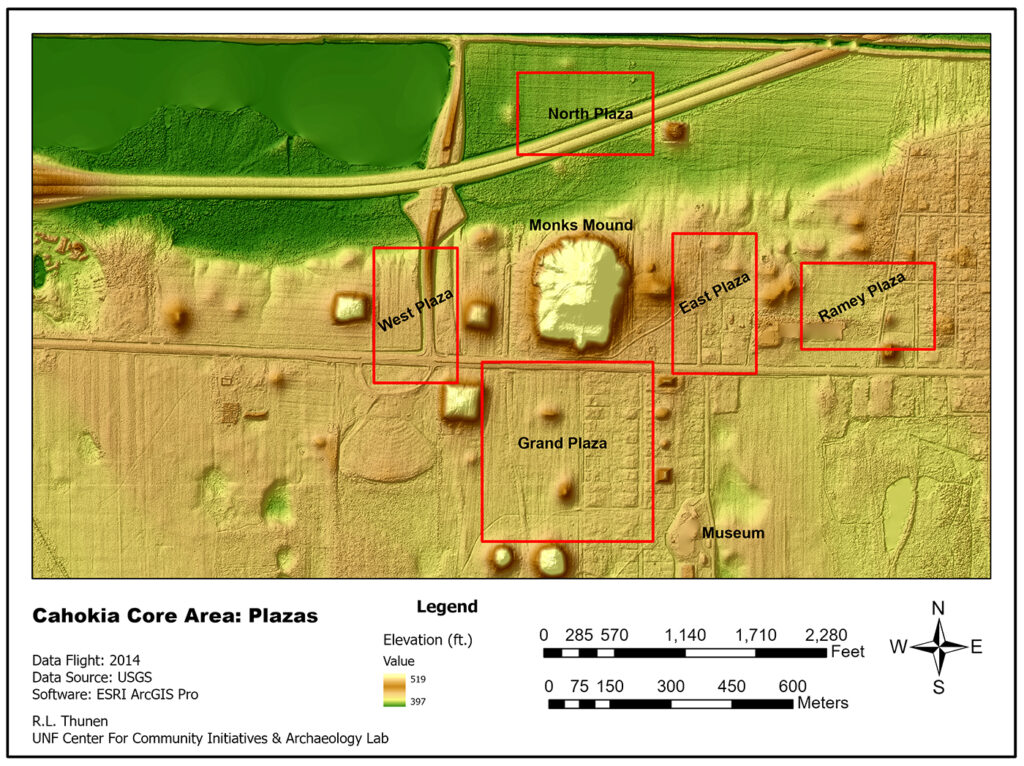

At Cahokia, archaeologists have defined at least five plaza areas within Cahokia’s core area (Figure 2). These plazas were structured around the Monk Mounds and located in the four cardinal directions. The plazas were bounded by circular and rectangle-based earthen mounds, often in pairs. Pedestrian surveys of the plaza areas by archaeologists have revealed a low density of artifactual material, suggesting that these were plazas rather than housing areas. Thus, archaeologists view these areas as central to the community’s ritual and political activities that brought people together across the American Bottoms for important rituals and social gatherings. Like the mounds, plazas were not static places frozen in time. The plazas have architectural biographies and stories to tell us: they are dynamic places with architectural history and differential use. Such plazas are often created over the top of former dwellings, activity areas, and even burials to create a new dynamic place, sometimes reorienting the nature of the site structure itself. Plazas can represent both the present communal and ritual occupation, and ancestral traditions through building, burials, flatten mounds, and community use. When those structures or activity areas were buried, their former ancestral use could sanctify the realignment or redevelopment and the new spatial use.

Today, many visitors view the mounds and plazas as static places as if they are frozen in time, “Pompeii like” yet nothing could be further from the truth, natural processes such as erosion, flooding, and seasonal change have continuously impacted these sites. Futhermore for native communities with ancestral ties to these sites, these sites are active, alive, dynamic, and present in the natural cycles of being and becoming. Contextually, past, present, and future intersect in these plazas. To this end, archaeologists are rediscovering plazas as essential to understanding the ongoing site’s history and cultural dynamics.

II. Cahokia’s Plazas

For the Lidar images in this post, I have added a hillshade layer underneath the elevation data to enhance the images. This layering allows you to see the roads, modern housing lots, and damaged areas for a more nuanced look at the areas. These five plazas were the platforms for major events in the lives of the Cahokians. Furthermore, other smaller plazas around the American Bottoms were used by kin groups within the various housing areas for kin-related rituals and activities.

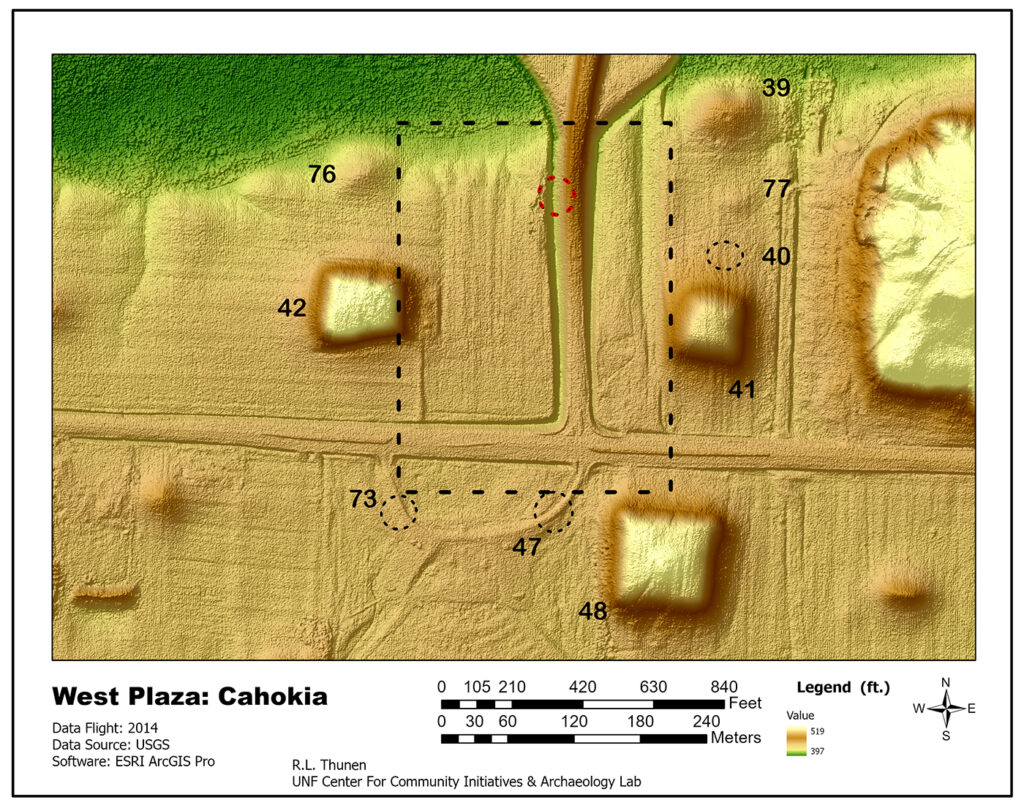

West Plaza

I start with the West Plaza (Figure 3), 9 hectares in area just west of Monks Mound. Four mounds (Mds 39, 40, 41, 77) define the plaza’s east edge. The north boundary is the south bank of the Cahokia Creek floodplain and by Mounds 39 and 76. The western edge is marked by Mounds 42, 76. Three mound locations, 40, 47, and 73 (dotted circles), show no topographic relief on the 2014 Lidar image. Melvin Fowler suggested that 47 and 73 have been buried or destroyed from constructing the Falcon Drive-in theater.

Previously, archaeologists did work in part of the plaza in the early 1960s as part of the construction of the Interstate and associated overpasses and off-ramps. Defined as Tract 15B, archaeologists just worked in the zone of the overpass and right-of-way, yet they defined important community and structural building information. Today, the plaza is bisected by the Sand Prairie Road overpass (see Figure 3). During the right-of-way excavations, several large structures and a “compound” of circular and large rectangular structures were uncovered. Of note were the bastions integrated into the walls of the rectangular structures making the structures very unusual for Cahokia. Please note the rectangular structures were not buildings but walled (fenced) structures, suggesting some specialized usage. The red circle indicates the area of the possible structure and the location of a possible mound.

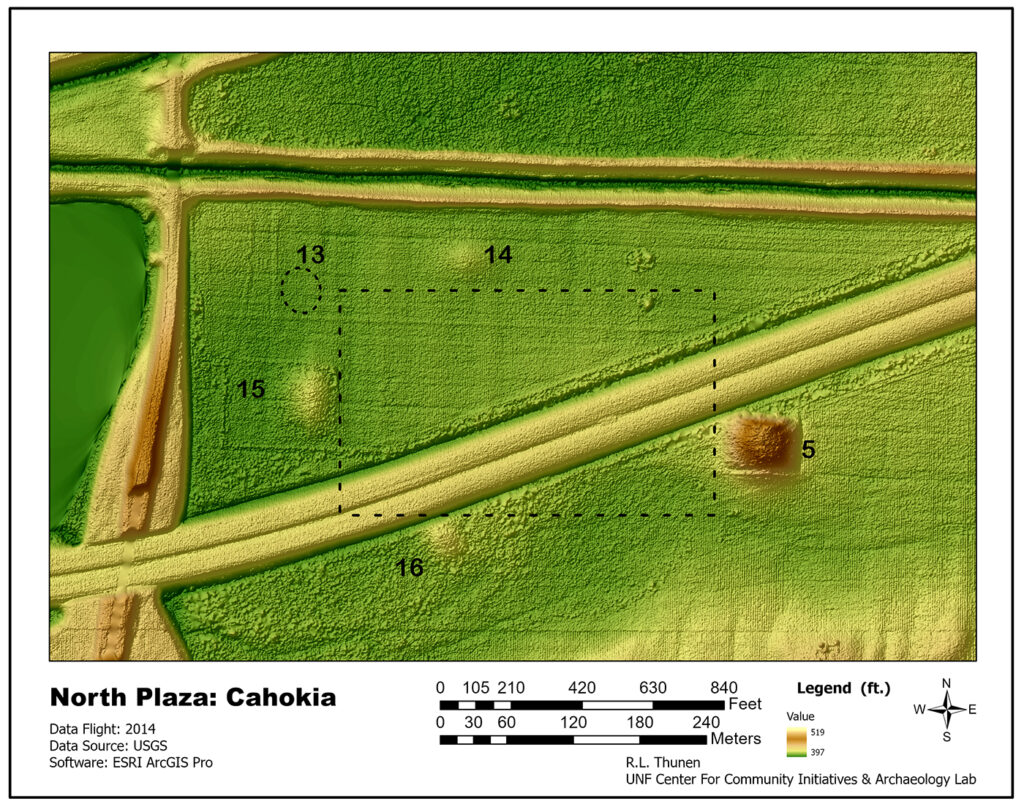

North Plaza

I turn to the North Plaza (Figure 4), the most enigmatic of the five plazas. It is enigmatic because of its lower elevation, closeness to wetlands and creeks, and the possibility of the plaza seasonally flooding during its occupation and use. An aquatic plaza? Five mounds define the plaza (Mds. 5, 13, 14,15, & 16). Mound 13 does not appear on the LiDAR because it has been plowed or eroded down. The Dwight D. Eisenhower Highway (Interstate 55/70) runs through the plaza, with the raised highway and drainage ditches on either side. To the west, the Sand Prairie Road borders the North Plaza. To the north, Canteen Creek (now a Canal and Levee) marked the northern boundary. Recent field research by Caitlin Rankin in 2017 uses sediment core samples and deep test units to examine different environmental and cultural areas within and outside the plaza. Based on the environmental and sedimentological data, her research suggests that the plaza was indeed inundated with water during the Cahokian’s occupation. A water-defined Plaza, whether by design or the result of changing environmental circumstances, is an outlier among the five plazas, and its function and possible symbolism will undoubtedly stimulate further research in this area. The research also demonstrated the importance of multidisciplinary research, especially using soil analysis to reconstruct ecological and environmental conditions. (See Rankin 2022)

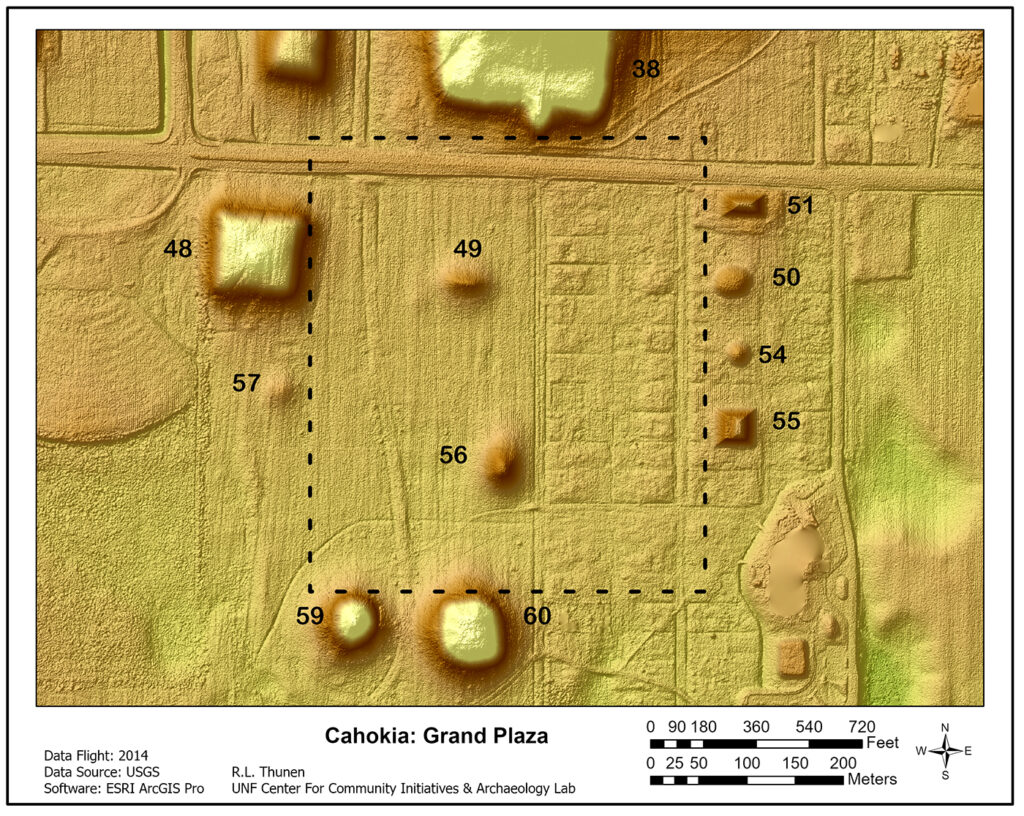

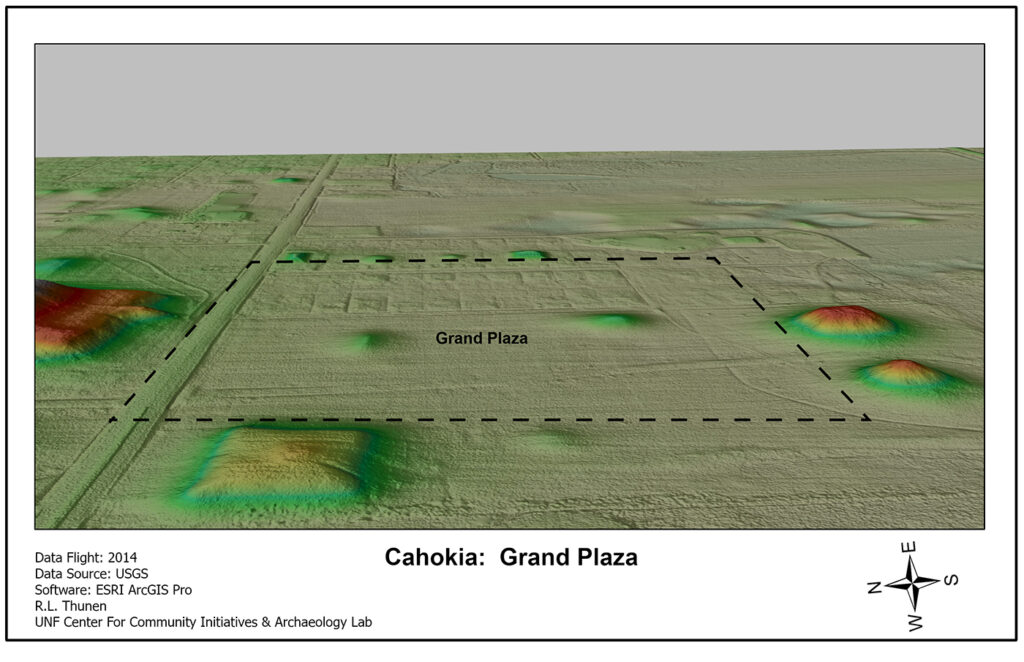

Grand Plaza

The “Grand” Plaza (Figures 5 & 6) is the largest plaza in terms of area, 19 hectares (47 acres) bounded to the north by Monks Mound (Md 38). Two mounds (Mds. 48 & 57) define the western edge. Cahokians built four mounds along the eastern edge (Mds. 50, 51, 54, 55). Two mounds (Mds. 59 & 60), known as the Twin Mounds, defined the southern edge. Finally, two mounds (Mds. 49 & 56) are centrally placed within the plaza. The LiDAR in Figures 5 & 6 shows that the plaza’s eastern half was used for a housing development before the park purchased the property. Several mounds along the east edge have been restored within the former housing development. Within the housing development, roads, ditches, sewer lines, and house foundations impacted the plaza’s surface. Agricultural practice also impacted the Cahokia site from at least the 19th century. The Great Plaza has been the focus of several archaeological and geophysical studies over the years, gaining essential knowledge about the plaza’s history and construction. Remember that Figure 4 shows the construction up to abandonment and represents the earthworks at the end of use.

Understanding the Grand Plaza’s development sequence of construction and use is an important aspect of the plaza’s history and its role in the larger Cahokia site. Several surveys have been done in the Grand Plaza. In 1997, a water main was planned to cross the plaza, revealing the entire plaza’s stratigraphy at one point. This was an extraordinary opportunity for the plaza in cross-section. Extending some seven-tenths of a mile, this trench helped to support earlier work by Rita Dalan, who did an electromagnetic survey in the Grand Plaza, documenting that the Plaza was a built structure not simplifying a flattening of the original surface. For example, (Figure 5) a sand ridge between Md. 48 and Md. 56 had been modified to help level and provide fill for mound building and/or the filling of several borrow pits in the later plaza area. I highly recommend Dalan et. al.’s book Envisioning Cahokia: A Landscape Perspective for further insights into both the use of remote sensing and applying a landscape perspective to Cahokia. It is a unique and important work among the Cahokia research studies.

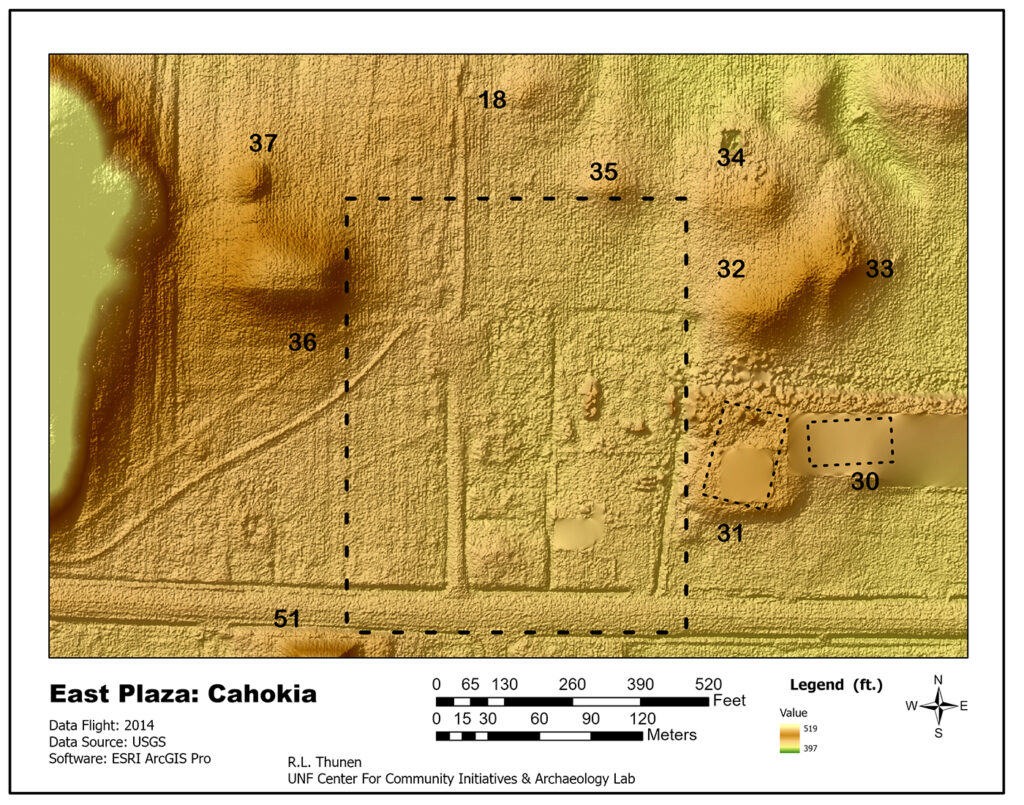

East Plaza

A couple of general but critical comments about the plazas east of Monks Mound. The first and most obvious is there are two plazas. Defined as East Plaza just adjacent to Monks Mound. (Figure 7) and the Ramey Plaza (Figure 8) further east of Monks Mounds. These two plazas demonstrate the dynamics and importance of plazas, planning, and social and physical investment. The East Plaza was created first, then, because of security, safety, and defense concerns, a wooden palisade or stockade was built around Cahokia’s core area. Twenty thousand posts, twelve to fifteen feet in height were used to build the wall and bastions. The wall was rebuilt three times, replacing posts as they decayed. Archaeologists have defined sections of the stockade wall; in fact, a section has been rebuilt in the original postholes in the East Plaza. Security concerns trumped the plaza, and the Cahokians moved the plaza further east; we call this later area the Ramey Plaza or East Plaza #2. Lastly, the East Plaza has undergone damage by commercial and residential buildings and by removing earth from the mounds for fill. In the case of Mound 30 & 31, they were leveled for the construction of a small shopping area (Grandpa Pideon’s Discount Store) back in the early 1960s. Today, the state owns the area and plans to remove the old buildings and restore the area to grasslands when money becomes available.

Mounds 36 and 37 define the plaza’s western edge along with Monks Mound. Mound 35 marks the northern border. Along the eastern edge, Mounds 31, 32, and 34 delimited the plaza’s edge. On the southern border, Mound 51 marks the southern edge. The plaza covers roughly 5.77 hectares (14 acres). All the mounds bordering this plaza have either been plowed down or used as fill; several have undergone archaeological testing as far back as the William Moorehead in the 1920s. Recently, James Brown (my dissertation advisor) and John Kelly went back to Gregory Perinos’ excavations from the 1950’s at Mound 34 and did more detailed mapping of Perino’s excavation, including mound stratigraphy and profile walls. For me, the most provocative work was done in an area off the mound known as the copper workshop, where copper nuggets were heated, and cold hammered into various ornaments and designs ( I will have more to say about the workshop later in a post titled A Tale of Two Artifacts).

Ramey Plaza

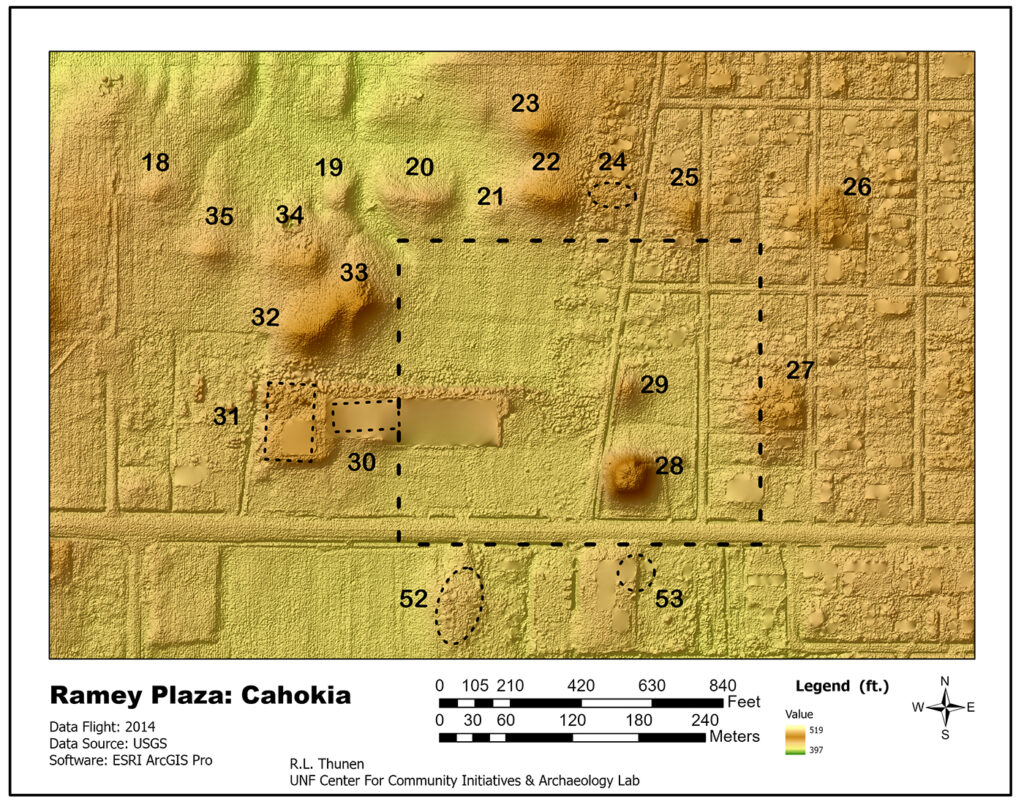

The Ramey Plaza was named for a local family that owned much of the site. Archaeologists consider this the 2nd plaza east of Monks Mounds. In Figure 7& 8 I have tried to place the eroded or badly damaged mounds in the correct locations based on earlier maps and reports. You can see the damage done to Mounds 30 and 31, which have been virtually destroyed, yet geophysical equipment may record beneath the surface an echo of the base of these rectangular earthworks. To the east, the housing development (State Park Village) has imprinted on top of several small mounds (MDs 25,26,27), and yet the elevation Lidar data marks these locations with a residue of elevation difference. This plaza, like the Grand Plaza, has two mounds in the middle of the plaza. And this brings us to two final questions: how do we define plazas:–as completely open space? And how do we define the plaza’s boundaries or borders? There are no easy answers, for we are viewing them as historical architecture and planning built and used over hundreds of years with fluidity of use, redesign, and renewal.

In conclusion, I have used Lidar here to demonstrate how it can be used to examine the Cahokia’s plaza’s spaces. An important lesson is Lidar does not and cannot examine below the surface’s elevation data. So, unlike the Shiloh Mississippian Mound Group, which had slight surface impressions, the Lidar at Cahokia does not “see” the foundations of the wooden wall around the core of Cahokia. The wave of future research will be increasing the use of geophysical technologies and Lidar to help us better understand and visualize the past.

References, Websites, Research and mentioned in this post

Plaza Research at Cahokia

George R. Holley, Rinita A. Dalan, and Philip A. Smith, Investigations in the Cahokia Grand Plaza, American Antiquity, Vol 58 No 2, pp. 306-319, 1993.

Caitlin Gail Rankin (2022) The exceptional environmental setting of

the North Plaza, Cahokia Mounds, Illinois, USA, World Archaeology, 54:1, 84-106, DOI:10.1080/00438243.2022.2077824

Caitlin Gail Rankin, Casey R. Barrier, Timothy J. Horsley, Evaluating narratives of ecocide with the stratigraphic record

at Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, Illinois, USA, Geoarchaeology, 2021;36:369–387. Wiley.

Interested in Geophysical Archaeological Research. Read these two important collection of research articles for North American

Jay K. Johnson, Remote Sensing in Archaeology. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa. 2006.

Duncan P. McKinnon and Bryan S. Haley, Archaeological Remote Sensing in North American. University of Alabama Press. 2017.

Books to read If interested in Cahokia and the Plazas:

Timothy R. Pauketat, Cahokia: Ancient America’s Great City on the Mississippi (Penguin Library of American Indian History) Paperback, July 27, 2010.

William Iseminger Cahokia Mounds: America’s First City (Landmarks) Paperback – March 3, 2010Biloine Whiting

Young and Melvin L. Fowler, Cahokia: The Great Native American Metropolis. University of Illinois Press. Urbana. 2000.

More Archaeological Books on Cahokia

Rinita A. Dalan, George R. Holley, William I. Woods, Harold W. Watters, Jr., and John A. Koepke, Envisioning Cahokia, A Landscape Perspective, Northern Illinois University Press, DeKalb, Illinois. paperback. 2003

Timothy R. Pauketat and Thomas E. Emerson, Cahokia: Domination and Ideology in the Mississippian World. University of Nebraska Press. 1997.

Notes: A future blog will deal with the geophysical survey of the plazas it is fascintating to see the results. Yes the Pulcher site was left off the Figure 1 map too far south.

Notice: The opinions offered here are the author’s and do not mean an endorsement by the UNF Archaeology Lab, Center for Community Initiatives, or the University of North Florida. A big thanks to my editor Dave and Word Press Designer Mike!